History of New Orleans

Need a primer on New Orleans’ long and storied past? Experience New Orleans offers a snapshot of what happened here in New Orleans, from the city’s founding to the present-day. Whether you’re a NOLA native or new visitor, we bet you’ll learn something!

Starting Out

.jpg)

The Gulf South was first inhabited by Native Americans, starting as early as 1000 B.C.E. This would be a pretty long history if we started there, though, so let’s fast-forward a bit! By the 1690s, fur trappers and traders had reached the region. In 1718, French explorers led by Jean-Baptiste Le Sieur de Bienville founded the colony of “La Nouvelle Orleans” in honor of Philip II, Duke of Orleans and then-Regent of France.

Life in the colony was tough, as New Orleans’ climate fostered disease and disaster, but colonists persevered. In 1722, after a hurricane flattened much of the colony, assistant city engineer Adrien de Pauger drew up plans for the 7-by-11-block rectangle that would become known as the “Vieux Carré,” or “Old Square.” This is where you can find a melange of New Orleans culture and architecture; a street is named in Pauger’s honor in what is now the Marigny area.

French, then Spanish, then back to French

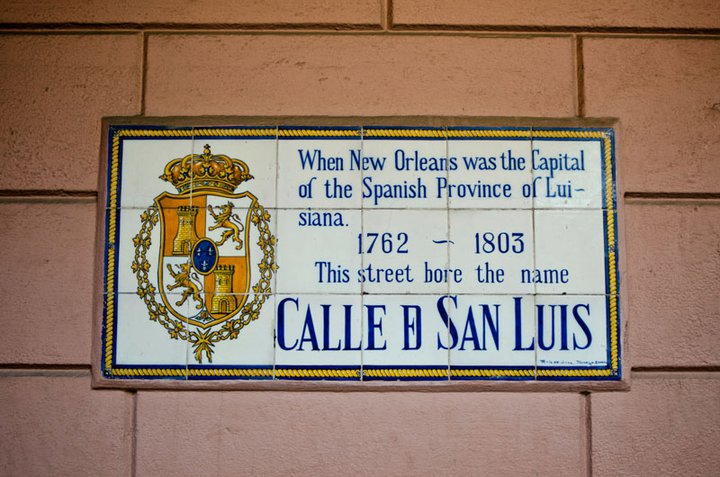

When Britain won the Seven Years’ War in 1763, Spain was given the land west of the Mississippi. As you can imagine, New Orleans’ mostly French population was not excited to suddenly be Spanish, and conflict broke out (read more about the defense of the city by reading about forts near New Orleans). However, New Orleans remained under Spanish control for 39 years.

During this short period of history, the Spanish were instrumental in making New Orleans the thriving port city it still is today. And after the Great Fire of 1788, much of the Vieux Carre was rebuilt in “second-generation Creole” and Greek Revival styles, with European courtyards that offered seclusion and privacy. “Madame John’s Legacy,” at 632 Dumaine Street, which survived the fire, is one of the few remaining examples of traditional French colonial architecture in the Quarter.

In 1800, control of New Orleans returned to France--but just for three years, because in 1803, Napoleon sold the entire Louisiana territory to the United States for the tidy sum of $15 million (about $233 million today: still a miniscule price for almost 900,000 square miles of land!).

American Rule and Civil War

Just one year after the Louisiana Purchase, the Haitian Revolution brought an influx of French-speaking immigrants to New Orleans, followed by another wave of immigrants from St. Domingue in 1809-1810. With French, Spanish, Creole, Acadian, African and now Haitian and Dominguan settlers, the city started to become a cosmopolitan destination, while remaining notorious for its wildness and frontier-like feel. By 1810, New Orleans was the largest city in the south, and the fifth-largest in the United States.

Louisiana became a state in 1812, and when America went to war against Britain just a few months later, General Andrew Jackson led an unconventional defense force to victory in the famous Battle of New Orleans. See a statue of Jackson at Jackson Square!

Despite victory against the Brits, New Orleans wasn’t as lucky when Union soldiers came a-knocking during the Civil War. Luckily, the city was spared the destruction that usually came with a Union occupation--otherwise, there wouldn’t be much to see!

Turn of the Century

By 1900, things were changing in New Orleans: French instruction in schools was fading, the city was fast industrializing, and the Creole elite were losing their prominence as New Orleans neighborhoods diversified with immigrants of all origins. More hardships were in store, including an outbreak of yellow fever in 1905--the final epidemic of the disease in the United States--that killed more than 40,000 residents.

Though much-anticipated, the 1884 World's Fair, or Cotton Centennial, in New Orleans, was mostly a failure. It opened two weeks behind schedule, and despite attractions like a Horticultural Hall with plants from all over the world, and a display of 5,000 electric lights. The site is now Audubon Park and Zoo.

But it wasn’t all bad. In the early 1900s, inventor A. Baldwin Wood created the screw pump, a powerful and ingenious mechanization that allowed New Orleans to develop much of the “back swamp” that surrounded the city. We still use the screw pump and its subsequent incarnations to drain low areas of New Orleans today!

Facing Down Difficulty

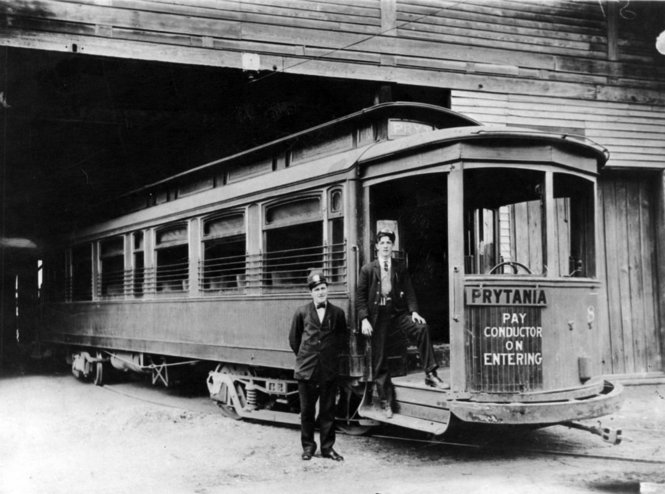

Despite its cosmopolitan character, French was still spoken throughout New Orleans at this point (and it’s the basis for some of the city’s unique “language”). The first few decades of the 20th century were hard on the Big Easy, with a decimating outbreak of yellow fever in 1905 followed by hurricanes in 1909 and 1915. There was at least one bright spot: in 1925, close to twenty private streetcar companies merged to create what we know today as the Residential Transit Authority.

Just two years later, the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 was a near-miss for New Orleans, with waters almost topping the levees while heavy rain still flooded parts of the city. This was also a sad period for New Orleans musically, when many heavy-hitting jazzmen left the city in favor of Chicago, New York and other Northern destinations, in what was called the “Great Migration”.

New Orleans played an instrumental part in the Allied D-Day victory at Normandy when local boatbuilder Andrew Higgins created the “Higgins boat,” or LCVP (Landing, Craft, Vehicle, Personnel; learn more about it at the National World War II Museum). After the war, the city’s swampy surrounding areas were successfully drained, and metropolitan expansion started to pick up speed, with growth in the suburbs of Metairie, Gentilly, and Lakeview.

Music and Progress

The second half of the 1900s held more economic progress for New Orleans, as well as an influx of Sicilians who brought a new flavor to the city (Angelo Brocato’s dessert parlor, a local institution dating from this era, offers many of these flavors, all delicious). The 1950s also saw the beginning of the return of many New Orleans musicians, and the advent of greats like Fats Domino, Mahalia Jackson, Irma Thomas, Professor Longhair, and the Neville Brothers. Hurricane Betsy visited New Orleans in 1965, blowing out windows and flooding more than 160,000 homes. By this time, New Orleanians were used to constant threats from the Gulf, but even with promised federal aid, it took weeks for some to return home.

More bad news followed in the years to come, as the city’s newly minted NFL team--the Saints--proved unsuccessful in most contests. But in 1978, New Orleans elected its first African-American mayor, Ernest N. “Dutch” Morial, who served the city for 8 years. It was around this time that tourism in New Orleans really began to take off. The 1984 Louisiana World Exposition, exactly 100 years after the quasi-failed Cotton Centennial, aimed to capitalize on the uptick in tourism, but like its predecessor, it was plagued by poor attendance. However, many New Orleanians enjoyed the fair’s postmodern architecture--especially the “Wonderwall” designed by Charles William Moore and William Turnball.

2000 and Beyond

When New Orleans entered the 21st century, we elected Mayor C. Ray Nagin, a former cable executive, to help us battle corruption in the city (little did we know he would disappoint in the difficult days and months following Hurricane Katrina). Lake Pontchartrain, long unsafe for swimming, began to be cleaned up.

On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina, in combination with storm surges, levee failures, and heavy rain, devastated New Orleans and surrounding areas. The ensuing days were dark. Almost 2000 residents died, and hundreds of thousands more didn’t know when or if they would be able to return home. Katrina was extensively covered in national and international news, but communication mishaps, fear and lost links in the chain of command made it difficult for New Orleans to get the aid we needed.

In the months and years following Katrina, many areas of New Orleans have rebuilt, with residents returning to their homes and businesses. It has not been easy--but New Orleanians have been through almost 300 years of hardship and hurricanes, and we were not willing to give up our city!

This is where most histories of New Orleans grind to a halt--as if nothing has happened here since Katrina. That couldn’t be farther from the truth. Much of New Orleans is back and better than ever, including our vibrant local music scene, our status as a world-renowned culinary destination, and the unique blend of cultures that has characterized our city from its very beginning. Since 2005, the city has seen a surge in local enterprise, including many neighborhood arts and farmer’s markets. In 2009, our beloved Saints won us our first Super Bowl, and we haven’t stopped celebrating since. Mardi Gras, Jazz Fest, and countless other festivals continue to draw visitors to the Crescent City; every day is a celebration of food, music, the arts, and the diversity that helps make New Orleans special. If you haven’t yet, it’s about time you experienced New Orleans.